Most of them were smitten with terror as with a plague. Every phenomenon of nature filled them with alarm. A thunder-storm sent them all upon their knees in mid-march. It was the opinion that thunder was the voice of God, announcing the day of judgment.

— Charles Mackay, Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1852)

Realistic or foolish, the global reaction to the novel coronavirus can best be described as panic. What the panic means is less clear.

Subsequent to the World Health Organization’s March 2020 declaration of a pandemic, anxious shoppers began hoarding essential household items, schools and Universities closed, officials banned public gatherings, the stock market went into conniptions, and whole populations have been sent into mandatory self-imposed isolation.

If Barack Obama was still President when this pandemic lockdown began, the American political right would be hopping up and down in their cages right now and throwing feces on the poor undergraduate research assistants who are just trying to feed them. Thank God we have a Republican in office, at least, so we don’t have to panic about martial law.

Every day, we in the industrialized world get gentle reminders not to panic while experts of all stripes take to the news, prognosticating apocalypse. And so everybody who listens to experts has begun to panic.

The panic, of course, could be predicted — especially with so many aspects of daily life quickly rendered uncertain: healthcare costs, income, rent … and, of course,we need to think about what happens to organized industry’s bottom line when individuals are forced to choose between the imperative to stay at home and the imperative to go to work.

Is there a hidden purpose behind the panic? Or, at least, an organized opportunism at play?

Pandemics happen. The word evokes great anxiety. The anxiety is almost mythological, and the present pandemic is routinely described in terms of the “Spanish flu” pandemic. Other pandemics — like the one in 1958, or 1968 — do not represent cultural scars the way the Plague, World War II, Vietnam or Iraq do. Putting a large portion of the industrialized world on some form of house arrest — while forcing a large portion of social interaction through a commercialized, digitally-friendly, behavior science lens — will have an effect down the road.

In 2009, the World Health Organization declared the “swine flu” pandemic. WHO Director General Dr. Margaret Chan made the “swine flu” pandemic announcement on the PBS NewsHour, seated in front of a giant statue of the Hindu god Shiva — the destroyer — dancing through the flames of the world:

After the “swine flu” pandemic was all said and done, the WHO came under criticism for its handling of the situation. Concerns that a WHO pandemic announcement “could cause worldwide panic and confusion” led to investigations by the European Council.

European policy makers held deep-seated “concerns about the possible influence of the pharmaceutical industry on some of the major decisions relating to the pandemic” because “the tentacles of drug company influence are in all levels in the decision-making process.”

But Shiva is not only the destroyer god: Shiva is also a creator god, able to display multiple aspects. As motivational speakers and influential think tanks like to say: disaster is an opportunity.

When the WHO declared the 2009 pandemic, governments and the bureaucrats that make them run were put on notice. As responsible parties stockpiled the antiviral drug Tamiflu, US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld personally profited somewhere between $5-15 million through his interest in Gilead Sciences. So don’t go into quarantine when opportunity knocks!

The administration of the “swine flu” pandemic sheds some light on the current pandemic, with respect to the politics of social control.

Economist Milton Friedman — known both as an economic adviser to President Reagan and for his work with the Chilean dictatorship — considered crisis a vital tool for policy makers. In Capitalism and Freedom, he wrote:

Only a crisis actual or perceived produces real change. When that crisis occurs, the actions that are taken depend on the ideas that are lying around. That, I believe, is our basic function: to develop alternatives to existing policies, to keep them alive and available until the politically impossible becomes politically inevitable

Following the 2009 swine flu pandemic, at least one medical researcher had taken cognizance of Friedman’s advice. Although media-induced panic was found to be a useful way to get one’s message disseminated, panic subsides and, should be followed up with a more comprehensive approach to policy implementation. In August 2010, the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine ran an article titled “Swine flu: is panic the key to successful modern health policy?” The article argues:

For any individual, one’s own body is a resolute ground of control, and care of the body allows one to maintain stability despite any risks associated with the outside world. It is no surprise that in light of mass media, government and health sector attention to the new H1N1/09 outbreak that individuals started to engage in more health protective behaviours such as hand-washing and avoidance of travel to affected areas.

On this evidence, it seems easy to argue that panic could play a pivotal role in successful modern health policy. However, the main difficulty is to instill a high level of anxiety and panic for a sustained period of time, as demonstrated by the finding that the time-length exposure of risk is linked to anxiety. Indeed, risk perception research has shown that people are more afraid of risks when they are brand new than after they have lived with it for some time…

In the New World Order, now that the Evil Empire is history and we have peace with the Taliban, we vote according to ideology, but big decisions are made according to the demands of crises. Crisis can be an effective way to frighten citizens into accepting policy changes they would never have thought to advocate.

After the events of 911, the US government imposed changes to air travel, new surveillance measures, invented the Department of Homeland Security, and fabricated a meaningless, unnecessary war in Iraq — all things that seemed unimaginable just a few weeks earlier. And all things that — combined with the threat of terrorism — maintained a consistent level of anxiety long enough for major policy changes to be enacted.

Our current crisis, for the most part, omits important discussions about risk. We know the magnitude of the pandemic, but what risks do we face as individuals? Is there a social or political “we” if everyone is to “go it alone” and quarantine with a cache of self-interested panic-buys? Come together by staying apart?

This past March, 3,580 Americans died with coronavirus particles in their blood, and 180,000 Americans were sickened by the pathogen.

This March, 3,166 Americans died in automobile accidents, and 366,000 Americans were seriously injured in accidents. We never discuss the automobile epidemic.

This march, 3,314 Americans died by firearm. We rarely discuss the firearm epidemic. When we do, it is in the context of lunatics and mass shootings; yet by far most firearm deaths are from suicide, domestic incidents, gang activity, and incidentally related to crimes compelled by poverty and misery.

We talk about the risks of coronavirus very differently than we talk about the risks of automobiles or firearms. And yet, when crisis can be invoked, politicians can exploit a spectacular month of automobile deaths on 911 (2,996 deaths) to justify lasting changes to our society and how we view civil liberties.

Coronavirus will pass, even though we are reorganizing our society around this new crisis. Some features of this crisis will stay with us. Americans are just starting to get ill, and corporations are already getting trillions of dollars in a massive feeding frenzy.

Just like the post-911 changes to air travel security are still here even though we don’t hear much about terrorists anymore, our current source of anxiety — germs — will put measures in place that will not be undone. The Federal Reserve’s response to this crisis relies on new policies enacted during the last one.

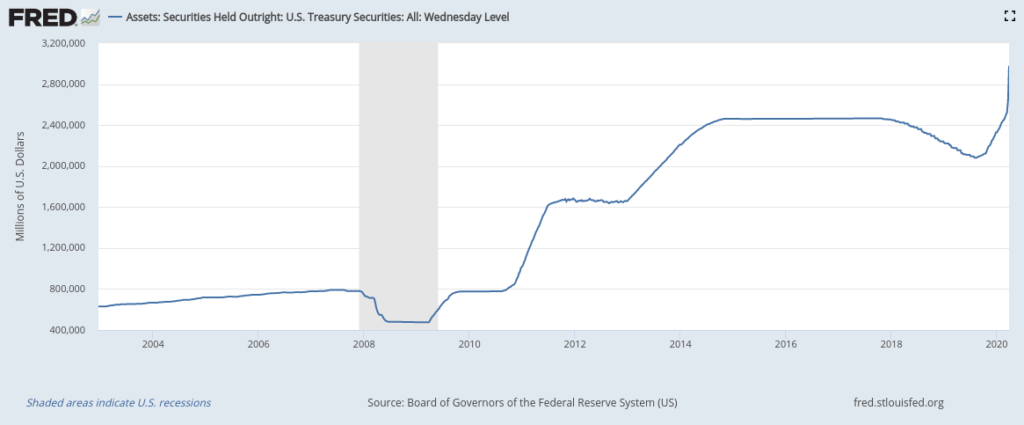

As much as coronavirus is a public health problem, it is also a wealth transfer which, between the $2 trillion authorized by Congress so far and the $4 trillion in new debt announced by the Federal Reserve, is already dwarfing the size of the bailouts from the 2008 financial crisis.

In other countries, the opportunism surrounding the coronavirus have ranged from sweeping emergency powers granted to the president of Hungary to an increase in nationalist sentiments in Italy, or grave uncertainty in countries like Greece, which harbor a large and disorganized refugee population.

As much as coronavirus is a public health emergency, it is also a transfer of wealth, a power grab, and, at its core, a massive social psychology experiment aimed at the prediction and control of human behavior.