The Western scientific program promises to reveal all the secrets of nature through systematic, rational inquiry. In so doing, it promises certainty beyond what superstition can muster and promises technological control over Nature superior to that of magic. As the technological products of science increase in complexity however, their intelligibility decreases. Technology is increasingly apprehended in terms of its “magical” effects, while the rational underpinnings become increasingly obscure.

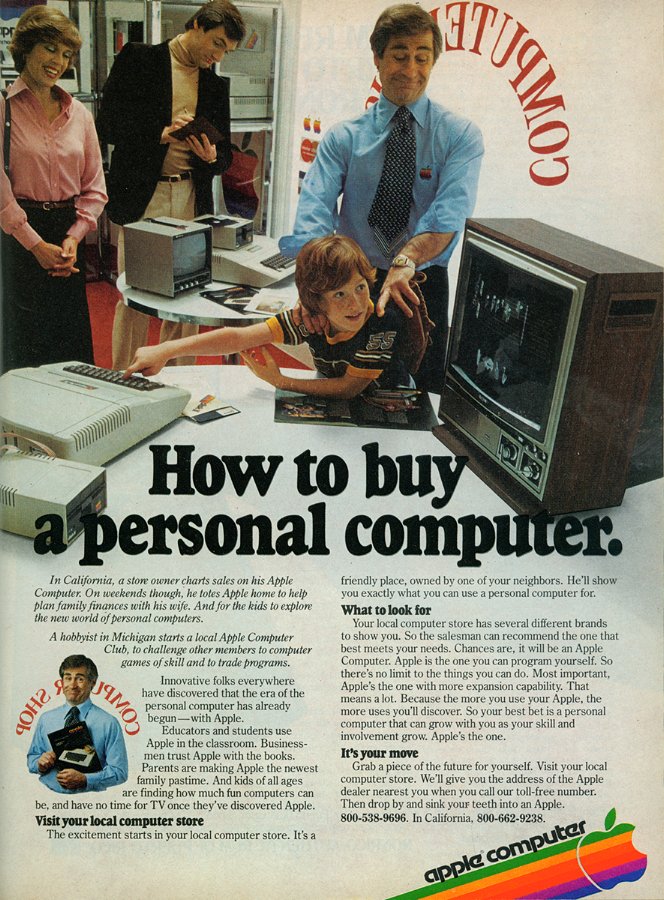

Science fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke opined that “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” Expressing a similar sentiment, psychologist Carl Jung wrote: “Magic happens to be everything that eludes comprehension… It is difficult to exist without reason… and that is exactly how difficult magic is.” In its current marketing campaign, Apple Computer offers products that are “practically magic,” enabling glossy photography without knowledge of exposure, and other like “miracles.”

Early signs of trouble in the European Enlightenment Rationalist tradition emerged around World War I. The Dada movement was not nihilistic, as is often charged, but a reaction against the moral vacuity of the modern scientific outlook, and a criticism of the notion that empirical science is an inherently a-moral enterprise. While modern science takes its philosophical starting point from Plato’s equating of Truth, Beauty, and Goodness, the advent of mechanized warfare and chemical weapons in the First World War caused a profound disturbance in the Western psyche.

With the nuclear arms race after World War II, the United States and the Soviet Union engineered a stalemate policy of mutual deterrence that continues to imperil all life on the planet, as satirized by Stanley Kubrick in Dr. Strangelove. Part of what sociologist C. Write Mills referred to as “organized irresponsibility,” the policy of Mutual Assured Destruction, or MAD, was devised by computer scientist John von Neumann, and modeled on the principles of game theory. For decades since, policy makers have essentially engaged in a hyper-rational planning regime for a technological apocalypse, where the flawed judgement of a single person can have catastrophic consequences globally.

Observing these developments in their infancy, Marxist psychologist Erich Fromm wrote in 1956:

“To speak of the ‘lacking sense of reality’ in modern man is contrary to the widely held idea that we are distinguished from most periods of history by our greater realism.”

“But to speak of our realism is almost like a paranoid distortion. What realists, who are playing with weapons which may lead to the destruction of all modern civilization, if not of our earth itself!”

“If an individual were found doing just that, he would be locked up immediately, and if he prided himself on his realism, the psychiatrists would consider this an additional and rather serious symptom of a diseased mind.”

Western science has largely delivered on many of the promises of magic, from practical control over matter at the subatomic level to the mastery of flight and tele-vision. Yet where sorcery is regarded as evil and dangerous, the rational products of science — which pollute, surveil, exploit and kill around the globe — are widely praised as the crowning achievements of our civilization.

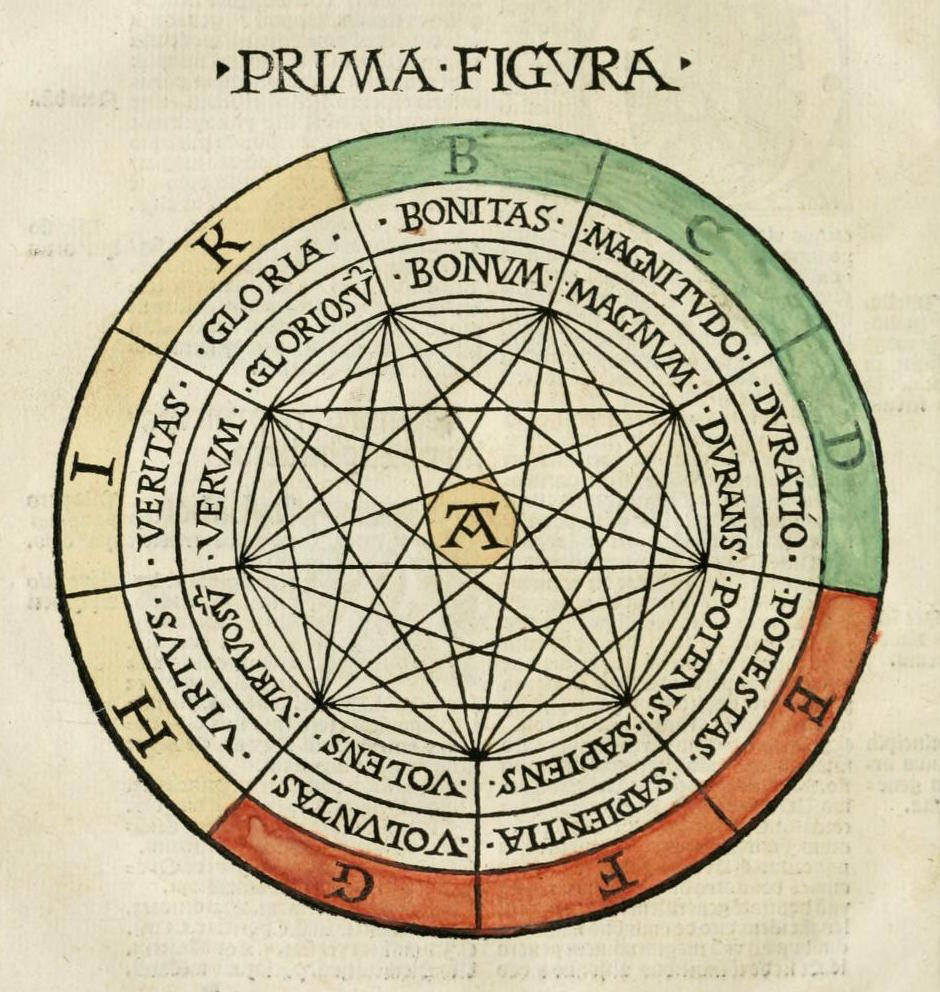

Beginning in the occult tradition at the interface of alchemy, Hermeticism, and the kabbalistic mathematics of religious thinkers like Abraham Abulafia and Ramon Llull, the return of science to “magic” suggests the failure of the Rationalist tradition is complete, and should serve as a warning that we are rapidly entering a new era of superstition and barbarism, as we gleefully destroy ourselves with a new “magic” few of us understand.