As a little girl weeps over the state of the US political process Mitt Romney fearlessly stays on message…

Tag: social media

Brands and Branded Identity

Consumers identify with their products. Sigmund Freud and Marshall McLuhan both theorized about the role of technology as a prosthesis — as an extension of the body — but many consumers today take this a step further, and internalize the messages used to market the products they purchase.

Through marketing, technology is not externalized, but internalized, and incorporated into the psyche. As such, it is less obviously an intrusion into the lives of consumers. Coming from the inside, it is less liable to be viewed in any way as an obstacle, and is thereby rendered a more effective means of manipulation, insofar as its influence is more difficult to discern or resist.

When consumers talk about how they “need” different products, they mean different things by this. Many people are quite dependent on technology generally: most products most consumers buy are products of industry. Food is no exception, even if it is served up at a locally-owned restaurant: most food comes from industrial agriculture.

In many cases, however, once a product has “gotten inside” the consumer, the consumer develops a psychological dependence on a product. Although addiction is a common metaphor used to describe this relationship, familiarity is also comfort. For most of human history, very little ever changed. In this era of planned obsolescence and pop culture, the brand — and, identification with branding — offers a source of continuity.

Consumers frequently purchase particular products because some symbolic quality of the product’s marketing provides a sense of comfort. While a particular smoker may describe himself as “a Marlboro man,” people also identify as “a Coke drinker” or “a Pepsi drinker.” Coke and Pepsi are both cola drinks, sold in cans and bottles, sold at an identical price point: they compete based on symbolism, not by offering more product at a lower cost. Consumers internalize the symbolism of marketing, and are conditioned to accept material products as related to these symbols — even if the connection between the symbol and the product is quite tenuous.

To the extent that consumers accept as their own views various messages offered up by marketers, individuals become little more than purchasing patterns: collections of brand preferences and demographic data. Individuals are branded by marketing, as with a branding iron. The degree to which this understanding of the individual has become normalized in contemporary society is revealed by the phraseology of politicians in describing the population: politicians talk about consumers with far greater frequency than they talk about citizens.

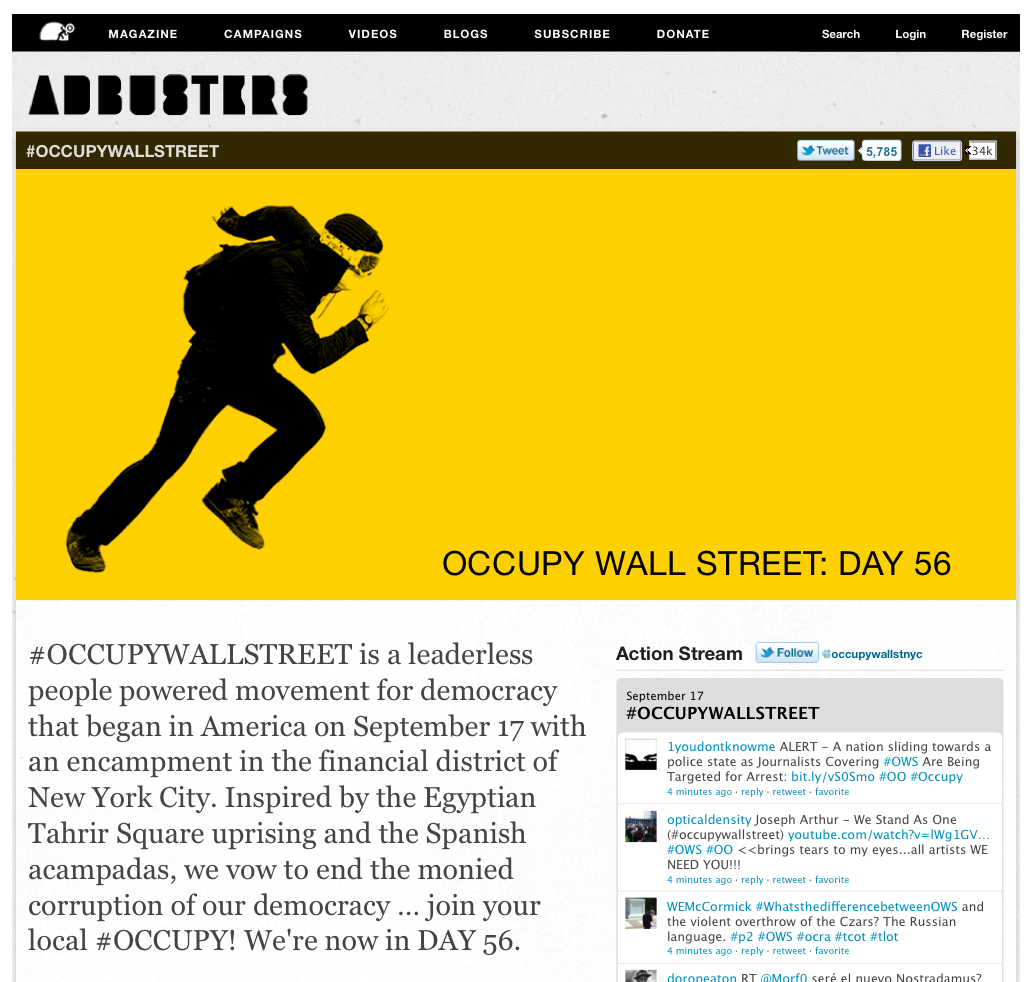

The phenomenon of brand-identification has social consequences as well: the “Twitter revolution” has seamlessly spread to the American social realm. That #Occupy Wall Street incorporates into its name a convention specific to a particular commercial service quite easily goes unnoticed, and is therefore accepted without question or objection. The revolution is an advertisement.

Tackling Fair Use

In late 2010, the NFL began to air a short promo during football games, which features grainy cell phone video of home audiences celebrating.

The video’s source footage, harvested from YouTube, includes scenes where members of the home audience pointed their cameras at their television screens during a game, in apparent violation of the NFL’s licensing restrictions.

Typical NFL broadcasts include the statement:

“This telecast is copyrighted by the NFL for the private use of our audience. Any other use of this telecast or any pictures, descriptions, or accounts of the game without the NFL’s consent is prohibited.”

The promo illustrates the arbitrary and capricious nature of corporate attitudes towards the distinction between “fair use” and “copyright infringement.” Commercial organizations such as late night talk shows, news broadcasts, and marketing firms routinely make use of footage that individuals produce and distribute on services like YouTube. The individuals who originate this footage are rarely credited, even in commercial broadcasts. At the same time, when individuals post commercial content to YouTube, that content is routinely removed.

Since the passage of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998, private firms have had a powerful tool to remove content from the Internet. The DMCA provides a legal framework for the issuance of a “takedown notice” which compels an offending party to cease the distribution of infringing content. This law has, however, been widely abused by businesses, often targeting small operators who don’t have the resources to determine whether a takedown notice is valid.

In a Spring 2009 statement issued through the Telecommunications Carriers Forum, Google claimed that 57% of the DMCA takedown notices it received were sent by firms seeking to frustrate competition, and that some 37% of the received takedown notices were not valid copyright claims.

Another noteworthy feature of this promo is the use of proprietary CBS trademarks in the status bar and on the field, as this spot is broadcast by competitors to CBS, such as Fox.

Every 7 Months, Another 3.2% of the World Goes on Auto-Pilot

¡Googol This, New Oxford American Dictionary!

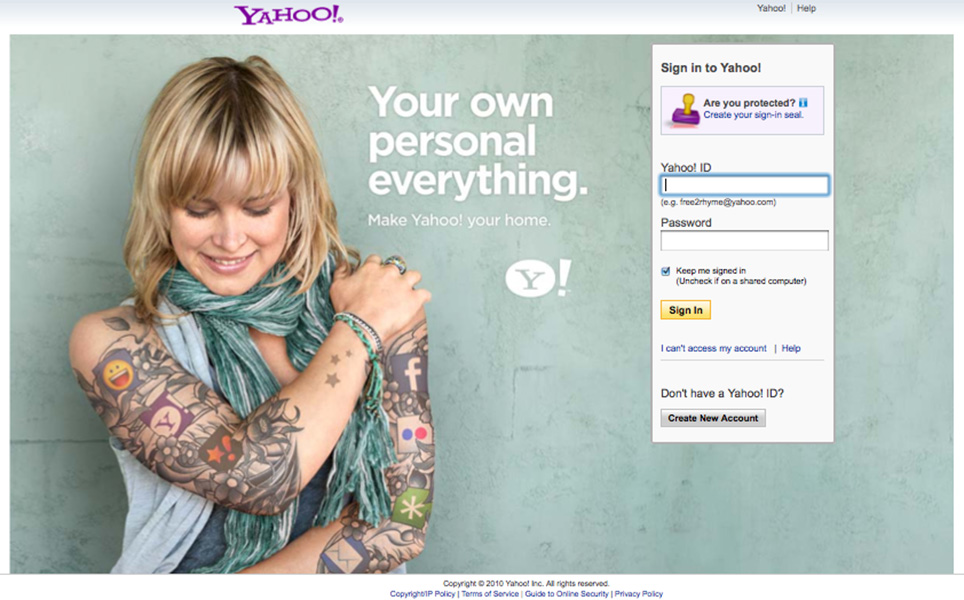

MySpace has introduced a major user interface overhaul; because the user base of MySpace includes both traditional consumers as well as producers of original content (and, in either case, suppliers of demographic data for advertisers), this change affects different users in different ways.

With a single advertising campaign, MySpace is both announcing the change and, simultaneously, providing a mechanism to monitor user reactions to the change. The advertising has, in a sense, been cast to the swarm, crowdsourced to the micro-blogging service Twitter.

The text to the left of the blue Go button as it appears in the ad above does a number of different things. First, it informs users that the changes to MySpace are more than cosmetic; the service has traditionally been a popular resource for cash-strapped bands in search of a media-rich web presence, but these latest changes to MySpace are in many ways oriented more towards the convenience of the service’s current (or prospective) media consumers. Information about pop culture and celebrities are pushed on users aggressively.

Second, the formatting of the text refers to the syntax of Twitter messaging: the # at the beginning of the text signifies that the attached adverb and proper noun will together function as a keyword or a tag for a post made with Twitter. Anybody can visit twitter.com and easily see all the posts tagged with the advertised text, making it easy for the MySpace marketing staff to, essentially, eavesdrop on a massive user discussion about the changes. MySpace doesn’t even need to put together a focus group because the Twitter makes users enjoy (or at least see no adverse consequence to) organizing their own discussion on behalf of MySpace.

Third, the reference to Twitter in the MySpace ad satisfies a certain postmodern cultural preference for referentiality. The referential qualities of the text’s formatting say new, hip, participatory, democratic. It’s a sort of techno-fetishism for the cult of progress. In a way, the advertising campaign for the new MySpace is not so much about the changes to the service (which are self-evident to a large number of existing users), but is more about the Twitter tag. If new users learn about the new MySpace, it will in many cases likely be through some other social media service (since, in the past, MySpace was not sufficiently reputable for continuous news coverage, while today, FaceBook is as popular as Google).

The discussion on Twitter varies in character, but gravitates towards various themes:

It’s fair to assume from the @ in the above Tweet™ that MySpace is actively monitoring the Twitter discussion. The above Tweet™ is furthermore genuinely diplomatic, offering constructive suggestions.

Many express basic statements of preference:

Others suggest the usage of basic features — which was once self-evident — has either been moved, removed, or counter-intuitively re-organized:

Some Tweet™s describe or advocate specific actions among MySpace users:

Occasionally, a Tweet™ will combine the advertised tag with other tags, treating the tags almost like semantic primitives (or even a little like ideograms built from a combination of Western punctuation and latin characters (and in some cases, Arabic numerals)):

Here’s a sample of some consecutive Tweet™s:

One new feature that caught my attention was the Discover button. Whenever your mouse rolls over the Discover button, the following appears on top of the new interface:

If you click the Next button in the lower right, the thumbnail images change:

Clicking on the Next button a second time produces this:

Which means, if you choose to engage with the Discover button by clicking on Next once, and then choose to continue by giving it a second click, after that second click, the Next and the Prev button are functionally equivalent. Once you’ve expressed enough interest to commit to a second click, the purpose of this interface element is to provide an illusion of choice.