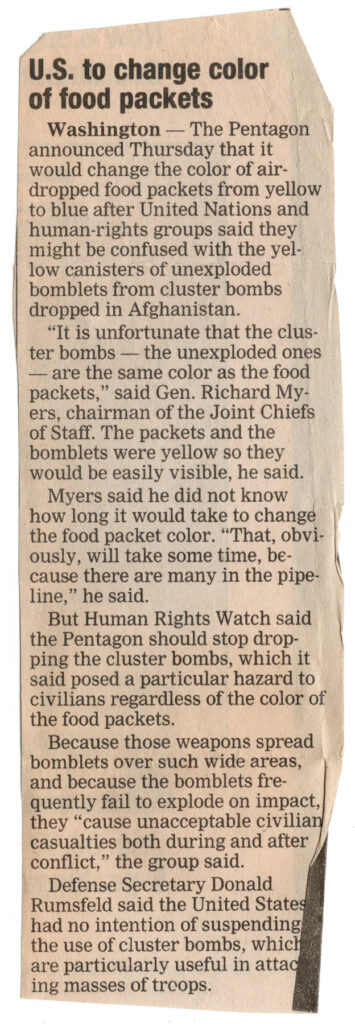

When the US invaded Afghanistan, a decade of conflict with the Soviet Union had left the country littered with more unexploded landmines than any other place on Earth. When the US began its invasion, we littered the countryside with unexploded cluster bombs, which were the same size and color as the food packets being airdropped.

At home, the enduring legacy of the rhetoric and hubris that led to the longest and most expensive conflict in US history should litter the airwaves and school text books as an edifice. Instead, the role of the media’s complicity in Afghanistan is sidestepped by the same few corporations that remain in control of the media landscape today.

As we appear to be running headlong into armed conflict in the Ukraine — negotiating arms transfers, coordinating economic sanctions, attempting to trap a desperate enemy in a corner — the lack of dissenting voices is quite disconcerting. After all, the Ukrainian conflict isn’t America’s war — yet.

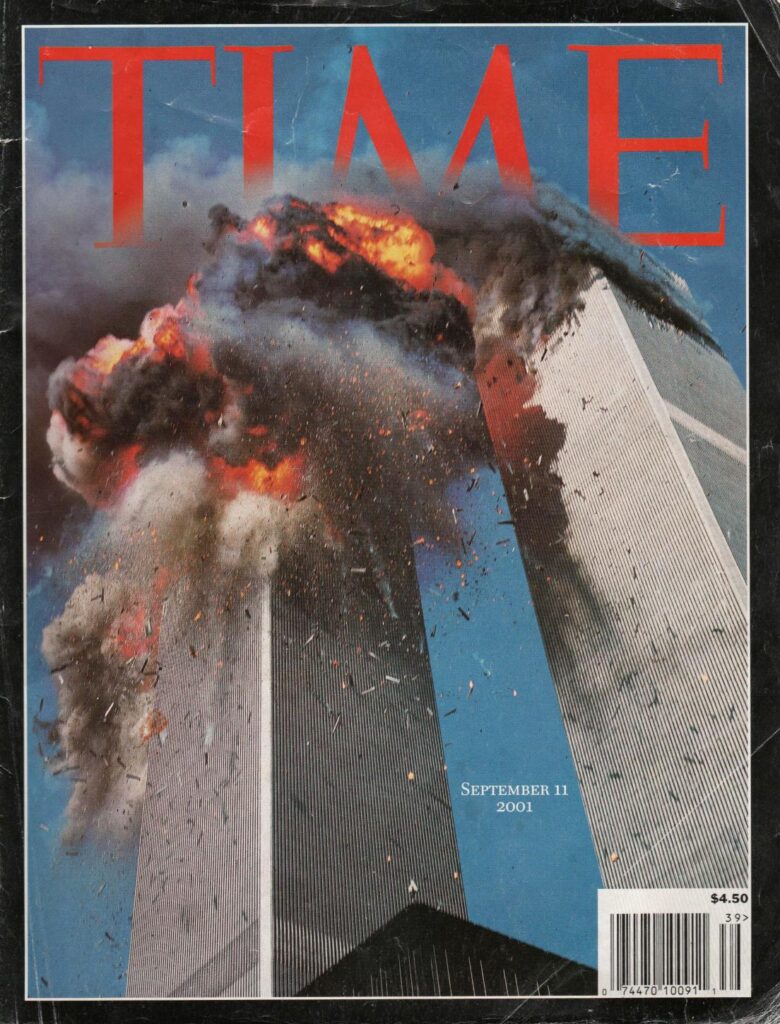

While commercial reporting outlets like Time Magazine can hardly be blamed for profiting from the events of September 11, 2001, many commercial media outlets instantly switched into pro-war propagandists.

Time was among many outlets that not only reported on developments, but also used their power and influence to steer America into the far greater disaster of the War in Afghanistan.

After an entire issue of Time Magazine filled with images of people terrified, rubble littering the streets, and tiny bodies leaping from the upper floors of the Twin Towers, on the very last page, Time published an editorial by Lance Morrow, titled “The Case for Rage and Retribution.”

In his editorial, Morrow argues:

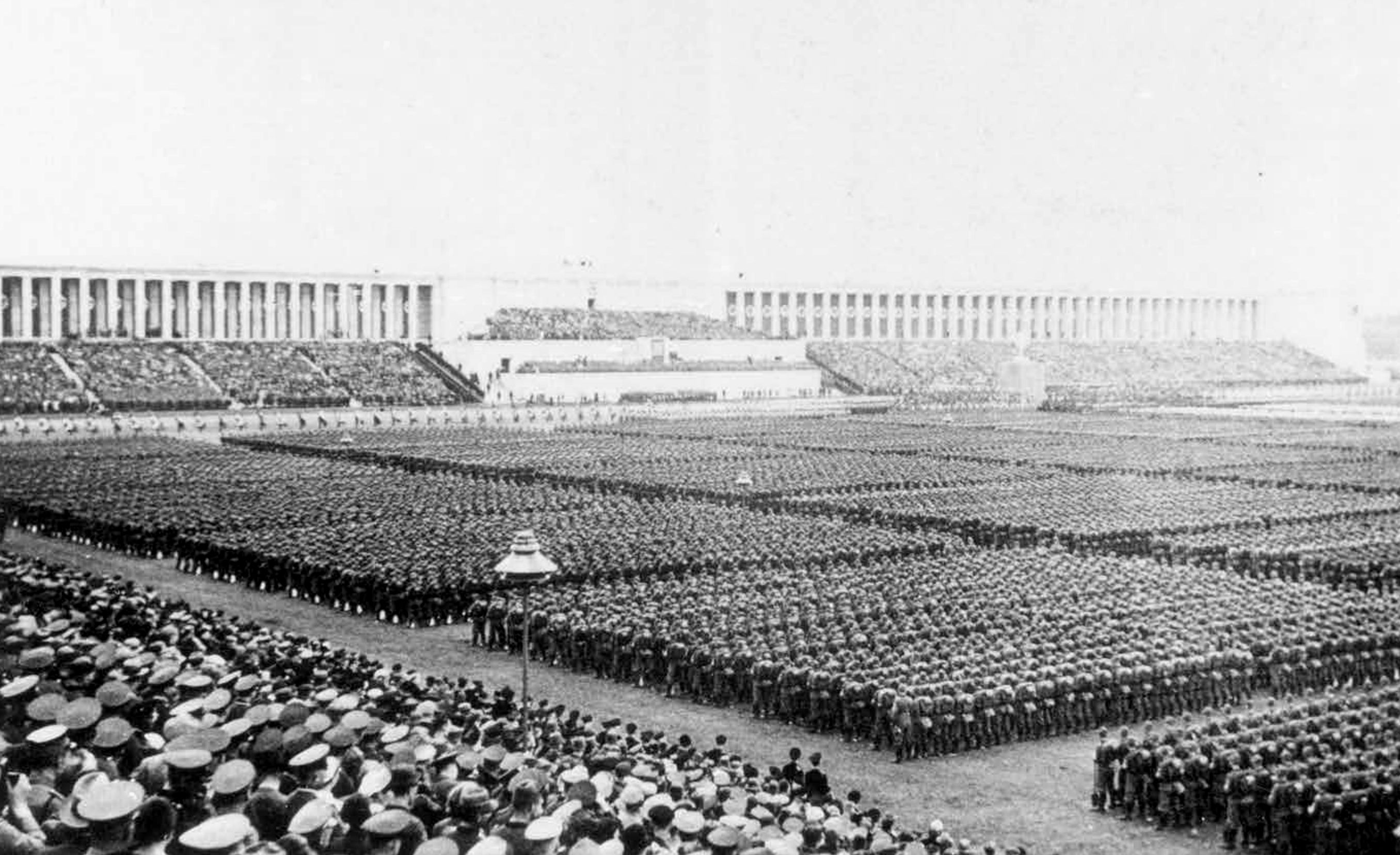

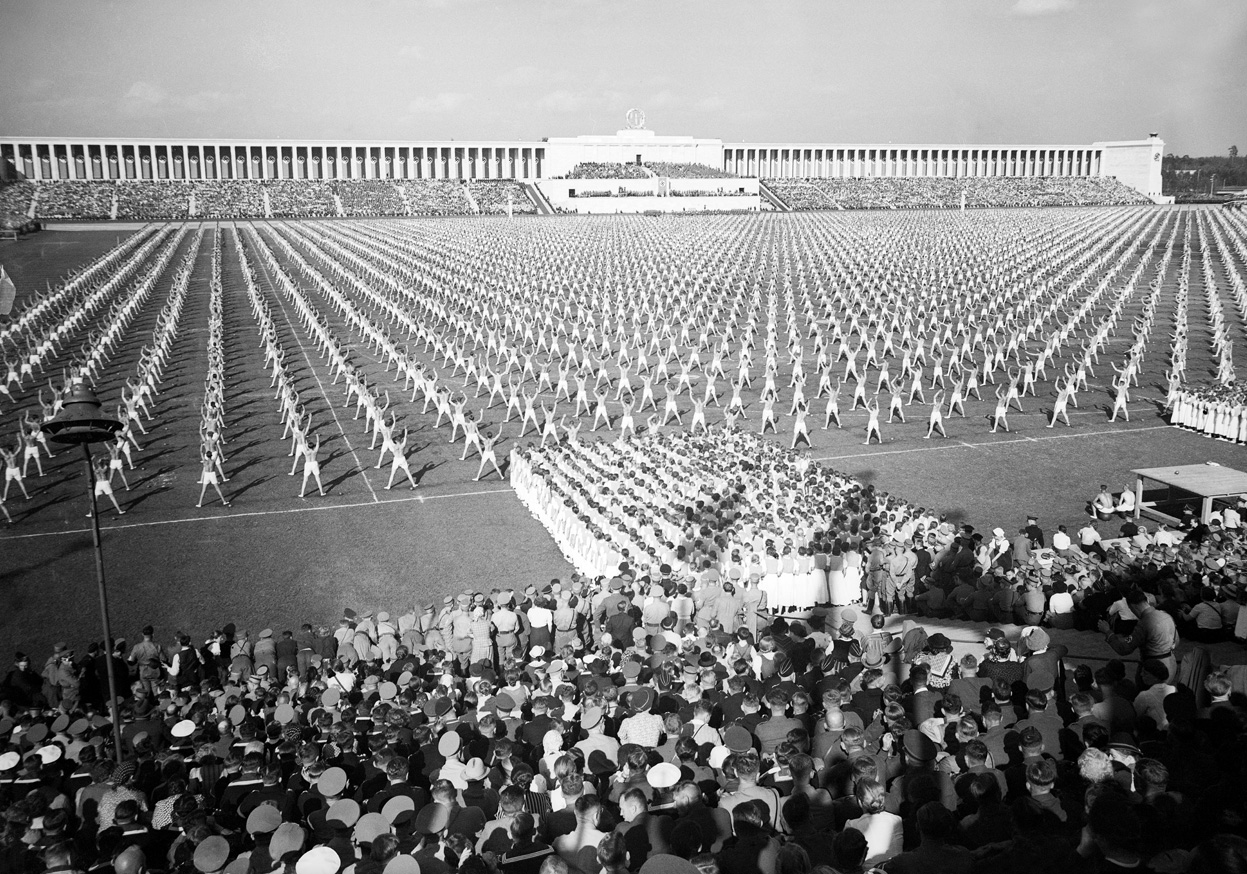

“A day cannot live in infamy without the nourishment of rage. Let’s have rage. What’s needed is a unified, unifying, Pearl Harbor sort of purple American fury — a ruthless indignation that doesn’t leak away in a week or two, wandering off into Prozac-induced forgetfulness or into the next media sensation … Let America explore the rich reciprocal possibilities of the fatwa. A policy of focused brutality does not come easily to a self-conscious, self-indulgent, contradictory, diverse, humane nation with a short attention span. America needs to relearn a lost discipline, self-confident relentlessness — and to relearn why human nature has equipped us all with a weapon … called hatred.”

From Lance Morrow, “The Case for Rage and Retribution,” Time Magazine, September 12, 2001.

With Morrow’s help, the United States certainly got “a ruthless indignation that doesn’t leak away in a week or two.” That indignation, however, required constant re-invigoration: even as Morrow is steering the US into a war that will be fought by Americans for an entire generation, he is almost scornful of the “Prozac-induced forgetfulness” of the “self-indulgent … nation with a short attention span.”

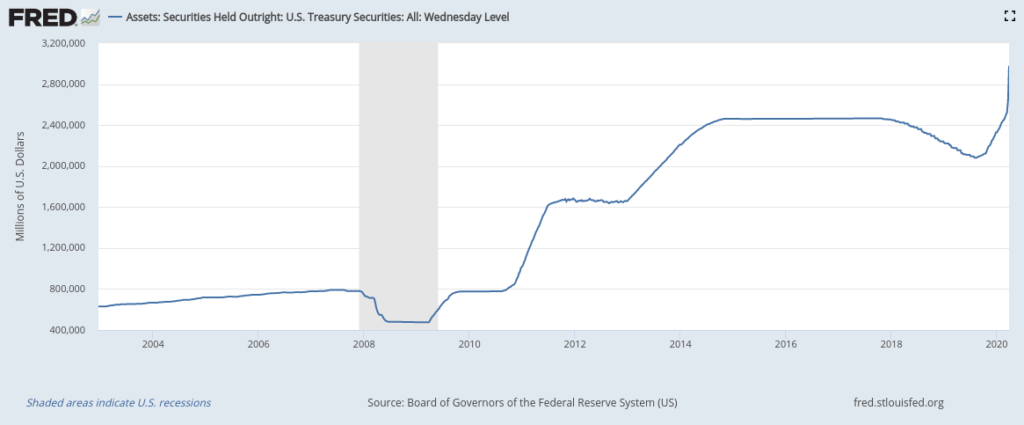

As a result of this contempt and manipulation, over 20 years, nearly 7,000 American service members and contractors died, over 66,000 uniformed Afghans died, nearly 50,000 Afghan civilians died, and over 30,000 maimed, traumatized, and brain-damaged US troops have killed themselves.

The contemptuous hubris blanket the US media landscape like unexploded cluster bombs disguised as food packets: journalists and media outlets ceased to be the lifeblood of democracy, and became deadly wolves in disguise, out for blood. In the war zone they were cheerleaders.

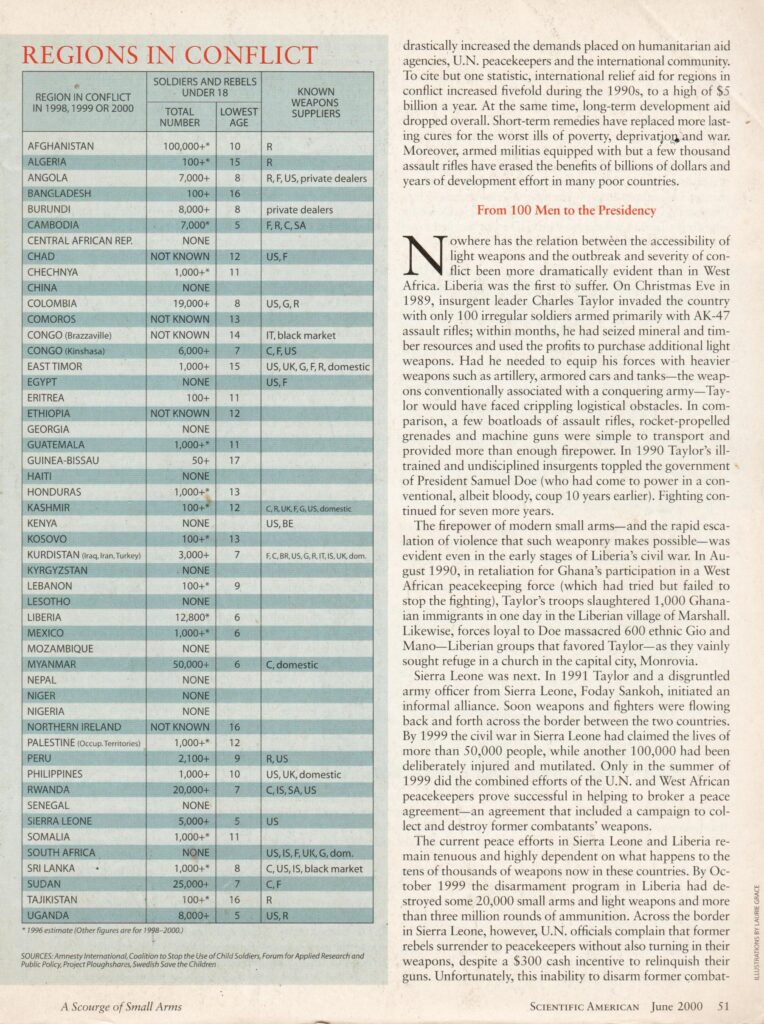

Journalists didn’t talk much about how Afghanistan had more child soldiers than any other conflict region on the planet at the time of our invasion. Journalists didn’t talk about how they had glorified Osama bin Laden and his anti-Soviet militia just a few years earlier. Journalists didn’t talk much about how Osama bin Laden wasn’t actually wanted in connection to 911, but rather, bombings in Africa. Journalists didn’t really talk about how the actual mastermind of 911 — Pakistani named Khalid Sheikh Mohammad — was captured and waterboarded almost 200 times at Guantanamo Bay. To prolong his torture — in violation of the Geneva Conventions and, likely, Nuremberg — interrogators used a special saline solution to prevent fungus from growing in Mohammad’s sinus.

Shortly after the US invasion of Afghanistan — at a time when all we knew of the conflict was “at least one American lies dead in Afghanistan” — Orlando Sentinel columnist Kathleen Parker penned an editorial titled “Terrorists Thrive on Pacifists.”

Directly addressing the pleas of that dead serviceman’s widow — who implored that “I do not want anyone to use my husband’s death to perpetuate violence” — Parker concludes her editorial, reminding us that “America does hear this mother’s pain and mourns her husband’s death. And no one wishes to judge her political beliefs during such an emotional time. But we should be clear: Pacifism in the face of terrorism is strictly an emotional response. Fighting back in this case is an act of purest logic.”

All of which served as a pretext for the invasion of Iraq — which had nothing to do with 911, but which has had a de-stabilizing effect on the region. Russia’s acts of war in Ukraine are couched in the most dire forms of moral condemnation — as if the US had not done the same sorts of things across Iraq. Beyond the shelling of residential areas with depleted uranium munitions, or the use of thermobaric bombs in Tora Bora, or the use of white phosphorous as an incendiary weapon in Fallujah, bodies were found with clear signs of torture — like holes drilled into the head — which hear the hallmark signs of the sorts of atrocities the CIA had pioneered in Latin America with the help of Nazi emigres.

If the US is pulled into a conflict in Europe, we may face a different sort of accountability than we faced in our recent Middle Eastern adventure. Were we held accountable in Iraq and Afghanistan, perhaps Putin would not be so bold now.

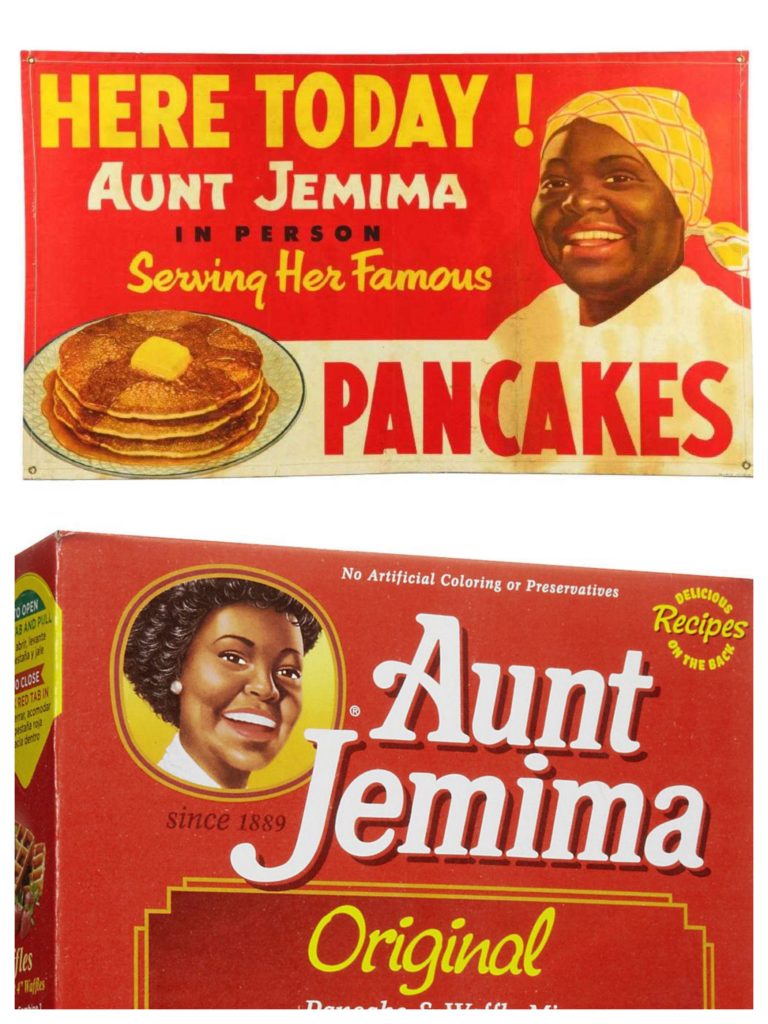

The United States is good at creating its own mortal enemies: Saddam Hussein ran a secular regime that recognized Western-style rights for women, and was once supported by the US. The Russian oligarchs now demonized by the US were largely created by former US officials at the World Bank and IMF like Lawrence Summers and Jeffrey Sachs The US once supported the militia it fought in Afghanistan.

Before we blunder into a military conflagration in Europe — where the rules of engagement and the consequences thereof will be different than in the Middle East — we might take stock of the moral failings of our recent foreign policy, lest we repeat our blunders less than a year after the official end of our failure and withdrawal from Afghanistan.